Theodore Roblee story.

-

Theodore Roblee at the World War II Memorial 2005

-

Theodore Roblee

- Theodore Roblee at the World War II Memorial 2005

- Theodore Roblee

The Theodore Roblee Story

Page 52

The Pilot ordered us to jettison all loose equipment to reduce weight. I gathered my flak jacket, steel helmet and the ammunition for my guns and threw them out of the front hatch. The crew did likewise.

When I returned to my seat, looked up and saw my first jet, just after I had discarded my ammunition. I announced on the intercom, “German jet, eleven o’clock high!” He was out of range and was just gliding out there. Hank ordered the crew chief to fire a flare, for fighter support, but he had already used them up. The Pilot then ordered him to fire whatever flares he had and he did. We must have been quite a sight; a crippled plane, straggling along, spewing flares of all colors.

Although it was pointless, I was tracking the jet, with my chin turret guns. He turned on his jets and shot from my left to right. I turned on the high speed button, but my turret couldn’t keep up with him, and then he was gone.

The tail gunner announced that four fighters were coming in on our tail. Everyone was excited, and all of us kept asking, “Can you make them out yet?” He finally, said they are P-51s. I waved to them, from plastic bubble, and they waved back.

A little while later, the tail gunner said four more fighters were coming in. This time, he identified them right away. They were P-57s, with their distinctive wide body. Unknown to us, these eight fighters must have formed an umbrella over us and that’s why the German jet left us alone. They saved our lives! Months later, when I spoke to the intelligence officer at our base in England, he told me the fighters reported nine parachutes, when we bailed out. They were protecting us to the very end, and for this I will be forever grateful!

Page 53

We were flying below 10,000 feet and I turned my oxygen off. The mask was still hanging to one side of my flight helmet. The Pilot had to use evasive action to get away from an anti-aircraft gun, so the Navigator lost our exact position. He handed me a ground map showing roads, woods, rivers, and etc., to try and locate our position. I was peering down at the ground, when suddenly, there were seven holes in the Plexiglas, something hit my left eye brow and blood was spiraling down my oxygen hose. I tapped my navigator on the shoulder, he ran his finger over the eye brow, and gave me the OK sign, with his thumb and index finger. The Pilot had assigned him to care for any medical problems aboard the plane. I don’t know if he had that kind of experience or if it was because the Red Cross medical kit was next to his table.

To get away from that anti- aircraft battery, the Pilot banked the plane on the dead engines and down we went. We leveled off at 3,000 feet and had lost half the power on the right inboard engine. We were over German occupied Northern Holland and could no longer make it to the English Channel. The question now, was should we make a wheels up crash landing, or bail out individually. The Pilot rang three bells; it was the signal to bail out!

Owen, the Co-Pilot, came down to the front escape hatch, wearing his parachute. He was twenty four, and the oldest, tallest and friendliest man on our crew. He was also, the only married man, and had a daughter. I learned, later, that because he was over six feet, he had to sign a waiver to fly on a B-17, which was designed for men of smaller stature. I, in contrast, was almost five foot ten at one hundred fifty five pounds.

Page 54

Owen pulled the emergency handle on the hatch, which was supposed to pull the two pins from the latches, so he could kick out the door. One pin came out, and the other, was partially jammed. Terry, the navigator, and I watched as Owen twisted the door off the hinge and bailed out.

The plane was quickly losing altitude and we had lost precious time. Terry bailed out and I was about to do the same, when Hank, the Pilot, ordered me to check if Wilson, the radio man was aware we were bailing out. He could have been busy on the radio. I called him on the emergency channel. There was no answer and I stood up and looked back through the plane. The wind was whistling through both the front hatch and main door. I told Hank, on the intercom, that we were the only ones on board and I was bailing out.

I glanced at the altimeter, we were at 750 feet. I squatted into “the cannon ball” position at the hatch and leaned out. I had the rip cord in my right hand and street shoes, which had been tied together, in my left.

We were supposed to count to ten before pulling the rip cord but there was no time for that. I remember counting one but I never got to two. When the chute opened, I was jerked into a sitting position. It looked like I was going to hit a wire fence, so I pulled on a shroud line but started coming down faster. I didn’t want that. I looked back and saw Hank’s chute. He must have put the plane on auto pilot and bailed right after me. I heard a loud explosion, when the plane hit the ground.

Page 55

I was coming down much faster than I had thought I would. My feet hit the ground first and then, my butt. It was a windy day and the chute was dragging me, on my back, across the field. I turned over to my stomach and grabbed the lower shroud to spill the wind out the chute. I had dropped my shoes when I hit the ground and went back to get them.

I was sitting on the ground, putting my shoes on, when a group of civilians surrounded me. They were speaking in Dutch and I did not understand them. One of them questioned “Tommy?” I answered Yes, as I knew that was slang for a British soldier. At least, they knew what side I was on. They picked up my chute and flying boots and went one way and pointed me to go toward the woods.

I ran, as fast as I could, until my chest started to hurt. I stopped in a culvert to rest and saw two men, in black uniforms, with rifles on their shoulders, coming toward me. To me, black uniforms meant, Gestapo, who we were told to particularly avoid. I got my breath back, immediately, and ran into the woods, where I was at ease. My father had sent me to Boy’s Camp for two weeks, each summer for seven years, and I had no fear of the “Great Outdoors.” I avoided the paths and found an evergreen tree, where I wrapped myself around the trunk, with the branches hanging down. In my forest green jumpsuit, I blended in perfectly. My hiding place as about seventy-five yards off the main path and I could observe what was happening. I stayed still and rested.

The German Army came down the path, with dogs and a large following of civilians. I froze when I saw the dogs. All I moved as my eyelids. The dogs did not have my scent and I hadn’t used the path. All the people helped. Was I far enough away

Page 56

from them? They kept moving down the path and it became quiet. I laid there for a long time.

In the lecture on evading capture, they told us to only approach a single person and never a group. If there was one person, that was pro German, no one would help. A lone woman, about my age, was walking down the path. I went through the woods to the path, in front of her, and hid behind a large tree. When she got close, I stepped out in front of her. She immediately checked my left eye. She spoke English, telling me to wait here, and she would bring help. I went back to my evergreen tree and waited. She came back with a young teenage boy. She said the boy didn’t speak English, but he had a place for me to hide, and I should go with him. He took me further into the woods to a newly dug grave and motioned for me to get into the grave. He showed me on his watch that he would be back after dark.

It was muddy in the grave. As I lay there, I heard a buzz bomb launched, toward England. There was probably a launch site nearby. These were motorized rockets, which flew over out base, all the time, on their way to London. When the motor stopped, the bomb came down.

I had been on a weekend pass, in London, when one of these was coming down. My lady friend and I ran to an air raid shelter. It was along concrete building with benches on each side. Most people, went toward the dim light at the far end, but we sat by the dark entrance and I kissed. I looked up, and there was an older Englishman, with a big mustache scowling at me. He obviously, didn’t approve. I don’t know why this would come to mind, but it did.

Page 57

It had been quiet for a long time, so I decided to smoke my last cigarette. While I was doing that, an older man with grey hair, looked into the grave. I immediately got up, but he was gone. Was he going to get the Germans? Why did I smoke that cigarette? I didn’t want to leave as the lad was coming to get me, after dark. There was an evergreen tree a short distance away and again hid, as I had before.

The grey haired man came back alone, and was holding something under his jacket. I came out and slowly approached him. If he was not armed, I felt I could overpower him. That was not necessary. He had a bottle of whiskey and poured me a strong drink and I got back into the grave.

After dark, the young lad returned and took me, through the woods, to an out-building in a farm yard. It was a pig pen with a section divided by a small fence, with little pigs on one side and clean straw on the other.

Two men in black uniforms were there. They had hats that looked like the picture, I had been shown of the Gestapo uniform and the one talking to me spoke perfect English. They said, they were Dutch Policemen and members of the Dutch underground patricians. They also said, they wanted to help me, when they saw me on the field, but I ran away and hid in the woods.

They asked, what was our Bomb Group and where out base was located in England? What was our target? What was my position on the air crew? How many men were on the plane? I gave them my name, rank and serial number and nothing else.

They told me that when our plane was coming down a farmer’s brother ran out to meet it. The plane crashed and exploded and the man was killed. My pilot, injured his

Page 58

ankle, and was trying to crawl away, when captured, just one hundred meters from our present location. The patricians had my co-pilot, Owen, hidden away and seven men were prisoners.

The Germans were still looking for me and had already checked this pig pen. They probably would not expect me to stay there, and if I was captured, I should tell them I found this place on my own and on one had helped me. I was not to remove the dried blood brow my face and eye brow to emphasize that point.

I asked for a drink of water and the young farmer brought me warm milk and a sandwich. The milk had been boiled and the skim was still on it. The sandwich was a thin slice of rough, brown bread with uncooked salt pork. I had never eaten uncooked meat before, but I would have this sandwich many times in the months ahead, sometimes, twice a day.

I drank some of the milk but said I was thirsty and really wanted water. They brought me imitation coffee made with chickaree, which I drank, but again asked for and received water.

These people had no electricity, no refrigeration, no coffee, since the war started and nobody drank the water. They were giving me what they had and people in the cities, were going without food. Harsh reality was coming to me as I lay down, in the clean straw, in my half of the pig pen.

I later learned that thirty four planes went down this day and it was called, “Bloody Sunday.” If they were all bombers, that would be 306 men!

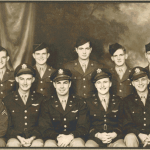

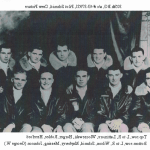

Theodore Roblee was a member of 365th Bomber Squadron, 305th Bomber Group.